Creating a Comprehensive Soccer Lesson: Training the Center Forward to Score

By Anthony Hazelwood

Soccer specific training sessions are performed on either an individual, small to large group or team settings. An important feature for all trainings is that player positions will vary, but functionality is key. Consequently, the construction of a holistic soccer plan for all environments should be of top importance.

The design of a comprehensive soccer lesson has the potential to produce significant player results when thoughtful and purposeful reflection is given to the following:

- The global positional attributes of the sport.

- The distinct roles each position schematically plays within a club/coaching philosophy.

- The technical-tactical aspects of the individual player.

- The physical expenditure via sport-specific movements associated with the sport.

- Mental and emotional aspects (mindset) needed for success.

- Injury prevention, movement preparation, nutritional and recovery protocols.

- Selection of suitable teaching methods to increase player performance.

For this article, the creation of an individual, functional, and comprehensive soccer plan, tailored for an elite level center forward will be touched upon. The session will focus on the following points:

- Improve the forward’s linear and multi-directional mobility patterns to shoot and score goals.

- Physically train the forward’s ability to recognize and repeatedly exploit the space behind the opponents back four when pushed at the half-way line or beyond.

- Target the anaerobic alactic energy system via maximal explosive sprints and multidirectional speed actions.

- Shoot at the goal while reacting to external stimulus.

- Defenders will not be present. Ball velocity and player sprinting speed to reach the ball will dictate training intensity.

- The variable and differential learning method will be selected as the teaching methods to develop player performance.

The Center Forward #9

The center forward is commonly known as the go-to soccer position to score goals. Characteristically, the striker is known as the ‘target man’ that gives depth to a soccer team’s formation.

Common attacking tasks of the center forward are (FFA, 2014):

- A key mission is to score goals.

- Possess a good shot preferably with both feet.

- Be a good header on the ball.

- Have keen spatial awareness and outstanding timing.

- Vision to perform various combination plays.

- Keep the ball under pressure from an opponent.

- The ability to take on defenders.

Although the above-mentioned features are subjective, it does mention the general commonalities the #9 is expected to have when training and competing.

To further define the roles of the center forward it is essential to consider the personal playing philosophy of the coach, the team, and the personal attributes of the player. Therefore, understanding the type of movements and responsibilities the player has within their squad is essential for proper program design. These specific roles and playing patterns will carve the movements needed to be trained during a session.

Tactical Movements: Mobility

In a soccer match, a team goes through different playing phases. The different phases include:

- Attacking (in-flow of the game).

- Transition to Defense. (in-flow of the game).

- Defending (in-flow of the game).

- Transition to Attack. (in-flow of the game).

- Attacking/Defending Dead-Ball situations (out of flow): Free-kicks, Throw-ins, Corners, etc.

When a team is attacking or transitioning to attack, the principle of mobility gives life to the tactical patterns of each player.

To improve the soccer forward’s movement speed during these phases, it’s important to understand the different types of speed actions the #9 will partake in:

Horizontal Linear Speed:

- Acceleration – Without or With Ball.

- Maximal Speed – Without or With Ball.

Multi-Directional Speed:

- Agility and Change of Direction Movements – Without or With Ball.

Progressively, the above movements must have a purpose and will be dictated by the type of on-field tactical soccer actions (overlapping runs, third man runs, movements to beat a defender, runs into space, etc.). Ultimately, these tactical mobility actions will be executed by a player and will be based on the team’s style of play and the current on-field situation.

Tracking the Forwards: Vectors

To understand common vector actions a center forward and soccer players perform in a match, turning to evidence-based studies can aid in this process. Example studies include:

- In a video match analysis performed by Osgnach et al. (2009) ‘‘sprinting’’, defined in studies as a running speed above a lower limit ranging from 19 to 25 km·h, amounted to 5%–10% of the total distance covered during a match (corresponding to 1%– 3% of match time). The average sprint duration was 2–4 seconds, and average sprint occurrence was 1 sprint for every 90 seconds (OSGNACH, POSER, BERNARDINI, RINALDO, & PRAMPERO, 2009).

- In a study by Andrzejewski et al (2013), the mean total sprint distance covered by all soccer players, at a velocity of ≥24 km·h, amounted to 237 ± 123 m. Forwards covered the longest sprinting distance at 345 ± 129 m. About 90% of sprints were shorter than 5 seconds and only 10% were longer than 5 seconds(Andrzejewski, Chmura, Pluta, & Kasprzak, 2013).

- In professional female soccer players, the mean sprint distances for forwards, at a velocity of ≥18 km · h, was 657 ± 157m (3). It also showed that forwards performed more sprints per match (43 ± 10) at the designated velocity than midfielders and defenders (Vescovi, 2014).

- In a study by Faude et al (2013), straight sprinting movement is seen as the most frequent action in goal situations. It is noted that power and speed abilities are important in decisive situations in professional football and should be included in fitness training (Faude, Kock, & Meyer, 2012).

The above studies give the needed information to create a plan based on the soccer players and a center forward’s movement actions. Therefore, preparing a forward to perform and repeat sprinting movements at an elite level is important for optimal performance during a match.

Training for Speed: The Energy System

Thoughtful considerations with the seen and unforeseen physical exertions the players may or will undergo during a competitive match are significant for proper training preparations. As previously stated, soccer players are considered repeated sprinting athletes. This is defined as (Bishop et. al, 2011):

- Performing high intense actions lasting ≤ 10 seconds.

- Brief recovery periods of ≤ 60 seconds.

To perform repeated sprints at a maximal level, the alactic anaerobic (ATP-CP) energy system, otherwise known as the creatine phosphate system, is identified as the energy system to be trained to make this happen. In soccer, this energy system is the highest in demand with the glycolytic and aerobic system being of moderate usage (NSCA, 2015). The alactic anaerobic system is accountable for providing the instant energy needed to perform the mentioned repeated sprinting activities. Joel Jamieson describes the creatine phosphate system as (Jamieson, 2009):

- Generates energy for 10 – 12 seconds at maximal intensity.

- Produces energy more readily than the other systems due to the fewest chemical steps.

- Active rest is best to augment aerobic recovery process.

Furthermore, different training approaches exist for training this energy system. For this session, the alactic capacity interval method will be used to train the center forward. By using this process, the outcomes include (Jamieson, 2009):

- Helps to improve the ability to maintain explosive power for extended durations.

- Improves max. capacity of the alactic system by increasing the amount of stored phosphocreatine.

With the above material, a soccer-specific work to rest speed session involving the alactic system can be created for the forward (Jamieson, 2009):

- Work Interval 10 – 15 seconds.

- Rest intervals are 20 – 90 seconds.

- Active Rest between series: 8 – 10 minutes.

- Volume: 10 – 12 reps per set for 2 -3 sets per workout.

Choosing a Learning Method

When implementing a soccer session, selecting a suitable teaching method is essential. For this training session, the main part will follow a variable practice method where open skills are practiced by repeating a skill (shooting at goal) in varying situations (linear, multi-directional movements). By using the variable teaching method, a whole-part-whole practice method will be used. This means an action is performed (whole), subjective teaching is taught to the athlete to aid a weak spot of the performed action (part) and then repeating the action again within the same parameters or with different movements (whole).

During the active recovery between sets, the differential learning model will be used. In short, the differential learning process is a philosophy that states: “never practice the right thing to play right” (Schöllhorn, Sechelmann, Trockel, & Westers, 2004). The basis of the differential method is that no movement is ever the same. Therefore, when trying to repeat a skill, there is little learning involved in comparison to introducing variances (noise) to that skill. These variances will put “noise” into an already learned pattern to increase the playing ability and applied comfortability of an athlete.

By using the differential learning model during the active recovery stage between sets, in this case for 8 to 10 minutes, it’s important to note that the technical skills will be worked on and there is minimal physical exertion as to recover.

Putting It All Together

Tactical:

- Improve the center forward’s mobility patterns to shoot and score goals.

- Improve the center forward’s ability to exploit space behind the opponents’ back four when placed at the halfway line.

- Attacking and transition to attack moments.

Fitness:

- Type of actions: Linear and multidirectional to linear speed actions.

- Set volume: 3 sets total.

- Work volume: 10 repetitions per set.

- Work interval time: 10 – 15 seconds per repetition.

- Rest intervals: 1:5 method. (e.g. 10-second action and 50-second)

- Active rest type between repetitions: Active Recovery – Jog back to place.

- Active rest between sets: 8 minutes.

- Intensity: High – Intensive Interval.

- Note: if an action is < 10 seconds, use the 1:5 method to calculate recovery period.

Technical:

- Proper corporal and ball handling techniques to reach session objectives.

- Proper linear running mechanics and multi-directional movements should be talked about if deficiencies are seen.

Psycho-emotional:

- Intensive actions to reach the ball at maximal running speeds.

- Use proper motivational skills to bring out the mindset needed for success.

Setup:

- Distances need to be at least on the half way line to create enough ground for 10 to 15 seconds of explosive maximal actions.

- Since we are training the center forward, actions should start and mimic what we want our center forwards to perform.

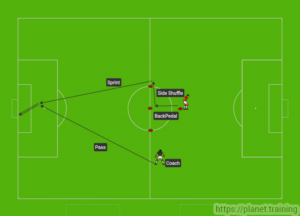

- Example Diagram:

Distances need to be far enough for players to achieve Maximal speed.

About the Author:

Coach Anthony Hazelwood is an Academy Fitness and Sports Performance Coach with the Major League Soccer Seattle Sounders FC.

Coach Hazelwood is a USSF “A” licensed soccer coach with an MSc in Sports Training and Nutrition from la Universidad Europea de Madrid (UEM), a Masters in Talent Identification and Development in Soccer from UEM, a Masters in International Sports Management from the Johan Cruyff Institute for Sport Studies, and a BSc in Physical Education: Sports and Fitness Studies from Florida International University (FIU).

He has previous European academy coaching experience as a soccer fitness and strength/conditioning assistant coach with the U/17’s of Levante U.D. (2013-2014) and the U/18’s of Getafe SAD CF (2016) in Valencia and Madrid, Spain respectively. Furthermore, he was handpicked by Javier Mallo (First Team Real Madrid Fitness Coach) and others to take part in a four-month observational coaching internship (Winter 2016) with Real Madrid CF in Madrid, Spain.

0 Comments for “Creating a Comprehensive Soccer Lesson”