Box Jumps: Higher the Better?

By: Lauren Green

I think I am what some might consider to be old school. I am not always using the newest slang or aware of the latest Kardashian news. But, I am trying to keep up with the times and engage in the ongoing growth of social media. It is proving to be a limitless platform for distributing and collecting information and ideas. From all over the globe, people are connected in unprecedented ways. This is an amazing tool that leads to creativity, innovation, and intellectual growth due to the ease of access to information and novel ideas. This can also be a very misleading tool. The “drive-thru” education model makes it very easy to misunderstand or mislead people; especially when it comes to training. It is very easy to glance at a picture or a video and assume you have mastered a training principle or philosophy. Why would you research an idea for yourself when someone just explained 10 years of scientific research to you in a 30 second Instagram clip, that’s just inefficient (note the sarcasm).

One of the greatest examples of coaches misunderstanding a training tool is the Box Jump. It seems like every time I look on a social media site I see someone else showing off their new PR (personal record) box jump. 42… 48… 54… 60 inches! As if accomplishing these jumps is the competition itself. Now I am all for having goals for training and celebrating milestones. That’s great. But what are we really celebrating? I want to shed some light on box jumps as a training tool and assessment, especially when it comes to youth athletes.

Why Do We Jump on Boxes?

I would like to think all coaches know why jump/plyometric training and assessment is used for youth and adult athletes, but just in case you are a novice coach I would like to recap.

Plyometric exercises are those in which a muscle group is put under a rapid stretch shortening cycle in hopes that the elastic nature of the muscles accumulates kinetic energy during the isometric phase that can be used during the concentric phase, thus improving the overall force production and rate of force development. By this definition, the result of a plyometric action is dependent on the muscles length/tension relationship, elastic qualities, tendon stiffness, and muscular strength through multiple ranges of motion. These qualities are dependent on each other and affect the outcome of plyometric movements. Luckily these qualities are also trainable. For example, weight training has been shown to improve tendon stiffness and muscular strength.

Sprinting, jumping, cutting, bounding, and leaping are all plyometric activities. They are found within every ground based power sport and an athlete’s ability to accomplish these movements faster than their opponent is a huge advantage. These are also the skills we coach and strive to improve within our athletes. Plyometric or jump training is used for this exact reason. Plyometric training can improve an athlete’s stretch shortening cycle, improve strength, increase joint stiffness, and improve overall jumping ability. By training to improve these qualities, we expect them to transfer into and be applied in real game scenarios.

What do we get from Box Jumps?

Faster, stronger, and more powerful. That’s how I got into performance training. I wanted to know how those great athletes did such amazing things with their bodies, and how I could replicate it. Well, of course we have to train. We need to get stronger, so we lift heavy things. We need to get more agile, so we run around cones and do fancy foot patterns. We need to jump higher, so we find something to practice jumping onto or over. Makes sense, right? But does this truly transfer on to the field or court?

As I previously stated, Plyometric movements utilize the stretch shortening cycle. And they do it rapidly. Muscles are eccentrically loaded with external force (usually body weight multiplied by the acceleration of gravity and momentum from the preceding movement). Then the muscle applies enough force to create an impulse (change in the direction of momentum), which is considered by some as the isometric phase. Then finally the athlete uses the momentum from the impulse to accelerate through a concentric muscle contraction and create force as rapidly as possible to apply all the combined forces against eh external load (i.e. gravity). A simple example of this is the counter movement jump. The athlete creates a movement by crouching down from a standing position, and counters the movement by creating an impulse somewhere in their squat and redirecting their momentum upwards to propel their body upwards as fast and hard as possible to get maximum height in their jump. This is the most common box jump exercise performed and the one we will focus on in this discussion.

While the counter movement jump is a very simple way of mimicking and practicing lower body plyometrics or jump training, doing it onto a box changes things. Plyometric movements are a 2-way street. Forces applied in the beginning of the movement (momentum), forces applied during the movement (impulse), and lastly the forces applied at the end of the movement (result of jump in addition to gravity). What goes up must come down. When we jump, we must land, and when we land we will land with the weight of our bodies multiplied by the acceleration of gravity. This means that we must have the strength to accommodate the force, especially if we need to repeat that action in succession and rapidly.

For certain scenarios, box jumps are a great tool to protect our athletes or simplify our training. If our athletes have attained a proficiency in the mechanics of jumping and landing, we can use box jumps to focus specifically on the jumping without the mechanical stress of landing. By landing on an elevated surface, we have taken away gravity’s ability to accelerate our mass and land on the box with a much smaller impact force. As eccentric muscle action is more fatiguing than concentric, decreasing the eccentric action and extra force while landing allows the athlete to execute more quality reps then they would while landing on the ground.

What if our athlete is not proficient in their jumping and landing mechanics? You might want to learn and practice landing if you are jumping. You don’t build a race car without breaks. Just as box jumps take away the eccentric forces of landing, the box depth drop takes away the extra work of the jumping action. The height of the box can be used as a tool to give you the height of your jump without having to execute the jump. This allows you to prioritize your training and focus strictly on the landing mechanics with more quality repetitions.

How We Abuse Box Jumps

As you can tell from the title, there are some misconceptions I want to clear up about the use of box jumps for training and especially their use for assessing progress. Out of respect for your time and my fingers, I want to get straight to the point. Jumping on a higher box does not equivocally mean you jumped higher! I know this is hard to deal with for some people because they were so excited to post their next video on Instagram, but let’s step back and take a real look at what is happening:

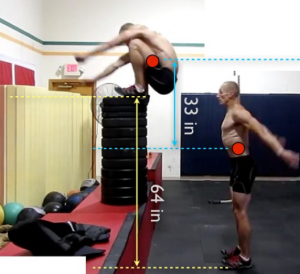

1. The height of your jump does not depend on a box. No matter what is in front of you or around you, the height of your jump will always depend on your ability to move your center of mass away from the earth’s surface by applying force rapidly against the ground and opposing the forces applied by the acceleration of gravity. Simply put, your jump height is determined by how high your center of mass (roughly your belly button) gets from its starting point when you were in contact with the ground.

2. The box is an absolute number while your ability to jump in it is relative. An athlete that is tall and light needs less force to jump a certain box height than an athlete that is shorter and heavier. The taller athlete starts with a higher center of mass and less resistance, while the shorter athlete has a longer distance to travel and more resistance from gravity because of it. The shorter athlete must apply a much greater amount of force to achieve the necessary height. So, what does a 48-inch box jump mean? Well it depends who you are asking.

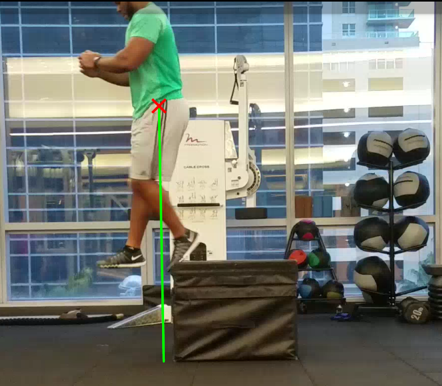

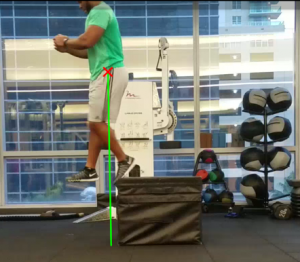

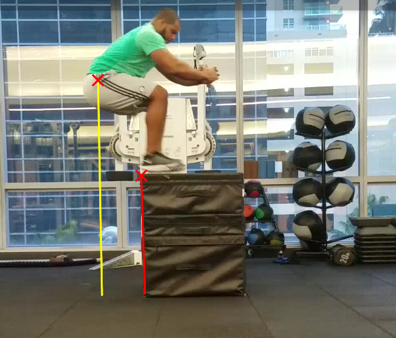

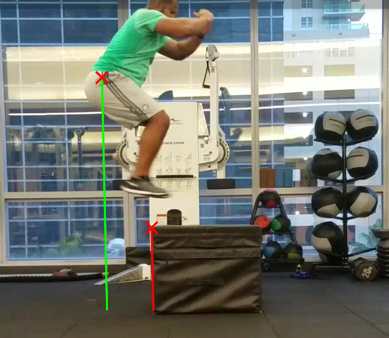

3. If you can’t land on the box in the same position that you jumped from, the box is too high. If the goal of your box jump is to practice deep hip flexion with poor posture, jump on the highest box you can find. The fact of the matter is your max box jump height is dependent on your jump height AND your hip flexion capacity. As I already stated, your jump height is independent of the box. At some point your jump will reach a terminal height (peak of your center of mass traveling upward), at which point you will recoil your legs and create as much hip flexion as possible to bring your feet upward. This is where the personal record box jumps happen, in increased gains in hip flexion. This isn’t a bad thing if we played sports that way. But if the key is to transfer the power on to the field or court, you are going to need to reproduce a similar movement immediately after landing. Also, the compressive forces at that range of motion throws the decreased mechanical work of landing out the window.

4. Did your youth athlete get more powerful, or did they just grow? Like the vertical countermovement jump, I have seen coaches use an increased box jump height as a training milestone for youth athletes. This might be one of the most misleading milestones out there. Youth athletes are always growing and changing. To be honest to the athlete and your training program, don’t take credit for natures work. If you have been training Billy since he was 12 and jumped on a 36-inch box, and now at 13 he can jump onto a 42-inch box; most likely he just grew and has a higher center of mass. This does not mean you didn’t improve your athlete’s athleticism or that your training program isn’t working. You just need to have a better assessment that has more precise and relative scores to compare.

Jump Training isn’t about the highest vertical or biggest box jump.

Learn how to jump train and perform box jumps correctly with Complete Jumps Training.

Does My Athlete Need Box Jumps?

I have been asked the question by new coaches (which is what inspired this piece); are box jumps good or bad? The answer is, yes. I always give the same answer to that question no matter what the exercise is. All exercises have a purpose and all stresses will elicit an adaptation. The question is whether the purpose of the exercise matches your training goal and if the athlete is responding with the desired adaptation from the stress? If your goal is to work on landing mechanics, a series of drops from boxes of progressing heights that eventually match the height of your max jump height is a great way to go about it. If your goal is to improve jumping ability, jumping on to the tallest box you can is probably not the answer.

The common factors between the plyometric movements (sprinting, jumping, cutting, etc) are strength, speed, and coordination. Athletes need to have strength to accept, respond to, and produce force. To be powerful an athlete needs to produce that force quickly, so coordination of contractions and rate of force development are factors that need to accompany strength. These are the qualities we need to train to improve an athlete’s ability to be powerful. The underlying factor is STRENGTH. This is true for all athletes, but even more so with youth athletes. As plyometric training, such as box jumps, is the practice of power; the athletes must have the foundations of power to practice it. If your athlete is lacking in relative strength, they will not reap the maximum benefits of the training and be left with holes in their preparedness. When the strength training has been established, plyometrics are a great addition to move the athlete along the Strength-Speed continuum. But strength is always going to be the limiting factor.

Related: Should Sprinting and Jumping Athletes Use Plyometrics?

Get your athletes stronger, practice recruiting the force faster, and get them into a position to repeat the action again. Getting your feet 60 inches in the air and on to a box does not transfer on to the field. Controlling your center of mass and moving it at high rates of speed does!

About the Author:

Lauren Green is currently the Assistant Strength and Conditioning Coach for the Brooklyn Nets of the NBA. Along with working with the NBA team, Lauren also serves as the Strength and Conditioning Coach for the Nets’ D-League team, the Long Island Nets. Lauren serves an instrumental role in the Nets Player development system, aiding the NBA team in the implementation of their Strength, Injury Mitigation, and Sports Science programs. Dually, Lauren designs and implements a similar program for the D-League team that prepares the players to transition and progress into the NBA team program.

Lauren Green is currently the Assistant Strength and Conditioning Coach for the Brooklyn Nets of the NBA. Along with working with the NBA team, Lauren also serves as the Strength and Conditioning Coach for the Nets’ D-League team, the Long Island Nets. Lauren serves an instrumental role in the Nets Player development system, aiding the NBA team in the implementation of their Strength, Injury Mitigation, and Sports Science programs. Dually, Lauren designs and implements a similar program for the D-League team that prepares the players to transition and progress into the NBA team program.

Prior to working for the Nets, Lauren was with the Los Angeles Dodgers of the MLB. Working in the Dodgers’ minor league system for 3 years, Lauren served as a minor league affiliate Strength and Conditioning Coach, and was named California League Strength Coach of the year in 2015. After the 2015 season, He was given the title of Latin American Coordinator of Strength and Conditioning. In this role Lauren was responsible for designing and implementing developmental programs that would prepare the Dodgers’ international, mostly from the Caribbean and Central/South America, teenage signees for the rigors of the American minor league system and culture of professional baseball. From strength training, arm care, speed and agility training to nutritional and cultural acclimation guidance, Lauren was given the responsibility of caring for and nurturing the organizations youngest and most impressionable players.

After obtaining a Bachelor’s degree in Physical Education from St. Cloud State University and a Master’s degree in Exercise Science from Concordia University in Chicago, Lauren developed a research-based approach to long term athletic development within his training philosophy and programs. Lauren is a Certified Strength and Conditioning Specialist (CSCS), and Registered Strength and Conditioning Coach (RSCC) through the NSCA. He is also a certified Performance Enhancement Specialist through NASM and certified Olympic lifting coach (USAW1) through USA weight lifting.

Prior to his career in professional sports, Lauren trained thousands of youth athletes in the private sector. From the ages of 8-18, Lauren implemented training programs to enhance the development of sport-specific skills as well as overall athleticism. Lauren displays a passion for the development process and its ability to influence the future by establishing a great foundation of training and understanding. Despite working in the elite professional levels as of late, Lauren is regarded as a development specialist.

References:

Osorio, D. (2014, September 8). 4 Common Exercises That Could Hurt Your Members. Retrieved from Inside the Affiliate: http://www.insidetheaffiliate.com/blog/2014/9/8/4-common-exercises-that-could-hurt-your-members.html

Recommended from Athletes Acceleration

0 Comments for “Box Jumps: Higher the Better?”