5 Ways to Get More Dynamic Transfer From the Weightroom to the Field

By: Joel Smith

A burning question amongst nearly any coach who spends time in the weightroom is: how do I get weights to transfer better to being fast and explosive on the field? As a strength coach who has seen various schemes of training fail and succeed amongst athletes whose sport is measured by the clock (track and field, and swimming), I’ve had a lot of opportunity to closely observe the movement patterns and abilities of stellar performers, as well as weight training schemes that resulted in faster times across the course of a season. I’ve also seen situations where athletes may have improved their maximal lifting output in the weightroom, yet don’t manage to get faster on the track or in the pool. Knowing the subtle, and not so subtle ideals of managing the weightroom are key to both the short, and more-so long term success of getting athletes faster and more powerful on the field. My career has been a huge learning process, and there are dozens of coaches and therapists who have played a huge role in the following five ideas that I feel are paramount in improving the transfer one gets from the weightroom, out to the field of play that I’m going to discuss in this article:

• Build explosive feet for explosive performance

• Repect the “Minimum Effective Dose”

• Shin and torso angles are the holy grail of squat and jump transfer

• Harness micro-potentiation and finish a lift session with speed

• Breathing and relaxation are keys to ultimate performance

1. Build Explosive Feet for Explosive Performance

The structure, function and training of the foot may be the least considered critical component of speed, agility and vertical jumping. The foot doesn’t get treated very well, or highly considered by many training programs. Locked in the cast of over-supportive shoes, and told to squat through the heels, over time, athletes can literally “squat their athleticism away”. I’ve seen it happen over time, as well as the aftermath of many high school athletes I’ve worked with in college who trained on extensive barbell programming in high school. These athletes came in strong, but their vertical jumps were often lower than their counterparts who hadn’t really lifted in high school, but could use their feet very well. What happens is that too much heavy squatting to full depth, cued through the heel puts athletes into heavy dorsiflexion under load. Tension through the forefoot is let out, and directed away from the big toe. Try this experiment. Take your shoes off, stand up, and do a squat to parallel with your weight on the balls of the feet. It’s OK if your heels even come off the ground a bit. Now try squatting with all the weight through your heel, and notice where the force on the foot goes. If you are like most, it goes towards the fifth metatarsal, the little toe, and away from the big toe. Squat like this too much, and wear restrictive shoes, and voila!, your feet start to disconnect from the hips, power leaks, and all that force you are building for the hips to output starts to dissipate. How to fix this? Easy: do more barefoot work, high rep single leg training focusing on centering pressure and steering force to the big toe, and use deep squats in a “minimal effective dose” format. We’ll get to this idea in my next point.

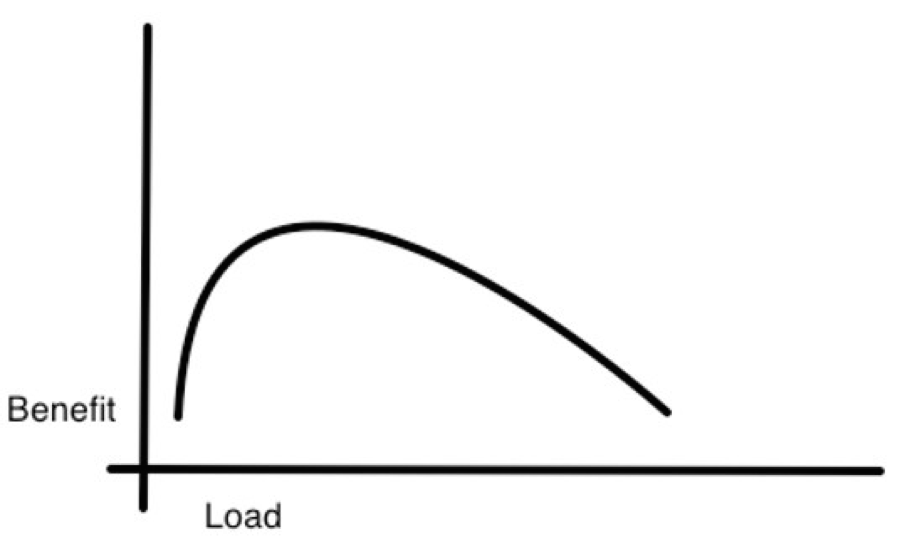

2. Respect the “Minimum Effective Dose”

Training is like a drug. If you don’t take enough, you won’t get a response. If you take too much, you end up in the hospital. As far as the land of training is concerned, most athletes are doing more lifting than what they can optimally tolerate as far as their total training package is concerned. On the other hand some athletes are part of programs where none of the lifting is intense enough to optimally stimulate either tension, motor-unit recruitment, or growth hormone stimulation as part of the program. There is a diminishing point of returns for athletes as far as training is concerned. What myself and other coaches have found, is that most athletes tolerance for strength training is not as high as their tolerance for speed and relevant sport skills. On the other hand, a strength athlete, such as a strongman, might have a very high tolerance for strength training, and a lower tolerance for speed work. We generally adapt towards what we are wired to do well. Here’s a hint: the majority of team sport athletes are wired to handle a good amount of stretch-shortening activity, and not so much strength work, relatively speaking. What myself, and other coaches are finding, is that single set lifting programs are capable of inducing the same strength gains as multi-set powerlifting programs, but with improved jumping and explosive sprint ability. Part of the reason for this is that when the 1-2 sets of an exercise are performed, they are performed with a high intensity, either in the weight on the bar, or the fatigue accumulated during the exercise, which taps into a broad range of muscle fibers and motor units.

In other words, in the weightroom, start with how little is effective, moreso than how much your athletes can tolerate. Personally, I won’t do more than 3 sets of any squat with the majority of my collegiate athletes, and I’ve even scaled back to 2 sets with some teams, but am finding that we still get great strength results, and are fresher for practice and explosive gains on the field of play. This attitude has seen fruition in numerous personal records, and even Olympic medal and world record performances.

On the other hand, the more explosive the exercise, I find athletes can tolerate more sets of it. We generally do more sets of explosive work, such as Olympic lifts, versus static work with many of my athletes.

The Dr Yessis 1×20 program and Pavel’s 2×5 program are good starting points for this idea, but any minimalist combination will work over time.

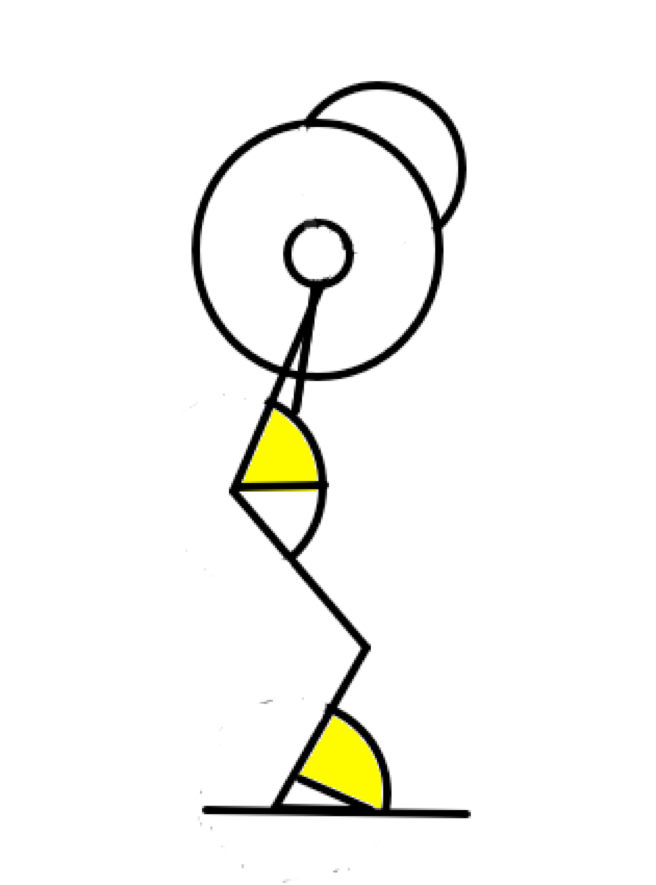

3. Shin and Torso Angles are the Holy Grail of Squat and Jump Mechanics

What I have found over time is that not all squatting is created equally. The idea of “sitting way back” while puffing the chest out is a highway to overemphasizing the lower back over-riding the glutes in movement.

Much of what falls into the world of strength and conditioning comes from the world of powerlifting, and low bar, hip back, vertical shin backsquats are the norm in many situations. Unfortunately, no athlete functions in a world of vertical shins.

We continually talk about how we need to train movements and not just muscles in the weightroom. Why then, do we put ourselves in positions that don’t resemble anything athletic. It is much more rare to see athletes on the line of scrimmage

At the first day of training, or during speed camps, I’ll often have athletes try to move around while keeping their shins vertical to the ground. Trying to move with the shins the same way we are coached to squat never gets anyone moving anywhere quickly.

Even in a clean, during the second pull, the knees are going to come forward to initiate a stretch reflex once the bar clears the knees. Olympic lifting isn’t just a mechanical deadlift to RDL to high pull, but rather, a symphony of reflexive, athletic movement.

“Watch what happens to the knees once the bar goes clear of the thighs”

Since some level of dorsiflexion is required, lifting should be done with some coached and understood forward translation of the shin. The easiest way to do this is to teach athletes the positioning of their shins, which should often match the position of their torso in movements such as squats and split squats.

In squats, the angle of the torso should be similar with the angle of the shin

This matching of angles does some great things, such as allowing an athlete to center pressure in the foot and engage the big toe, keep more tension in the glutes, bring the spinal erectors into a proper length, and more.

4. Harness Micro-Potentiation and Finish a Lift Session with Speed

I heard a statement from Vern Gambetta years ago that “the last thing you do in the weightroom, your body seems to remember going into the next workout”. I’ve also seen successful NCAA jumps coaches who swore by doing a series of plyometric exercises right after a strength session because they felt it help them recover better.

Not only can explosive work, such as plyometrics be good at the tail end of the workout, but infusing the workout with high rep, rhythmic and explosive work will improve the overall effect of training in the direction of speed and power.

Additionally, I’ve seen the practice where track coaches would even “reverse” the order of training to break through ruts and plateau’s. For example, instead of the traditional “Speed, then plyos, then weights” approach to training; or, as far as team sport might be concerned, practice, then weights, the order is flip flopped. When you arrange things into: Weights, plyos, speed, each means actually potentiates the next, so long as you don’t go too far beyond the effective dosage of each training mean.

Not only can barbell training improve a subsequent power session, but power can also be infused within the course of the workout in many cases (i.e. complex training). I often prefer the pre-season as the best time to do this, where in season-work is more about stabilizing skills and the gross (workout to workout) potentiation effect of strength work rather than in-session effects.

Some strategies I’ve utilized over time that I found effective in helping athletes to leave the weightroom, and enter the next training day with a bit more “bounce” have been pieces like the following:

- Finishing the workout with 5x80m sprint strides on the grass

- Finishing a workout with 2×15 jump squats with barbell weight only, and 2x20m barbell skips with 45-95lb

- End a workout with a short series of multi-jumps and throws, such as standing triple jump, and a vertical medicine ball throw for height. Be sure to keep a quick pace to the movements

- 30 second maximal speed rope/broomstick hops as part of a lifting or power circuit

- Descend from “heaviest to lightest” over the course of a workout, such as going from deadlifts, to cleans, to snatches (the old BFS jump training sequence), or do French Contrast training (complex training alternating heavy strength and light speed exercises).

- Infuse sled pushes in with your explosive pulls (deadlifts, cleans, high pulls, etc.), and do so in a dense, “every minute on the minute” training package to improve neural efficiency

5. Breathing and Relaxation are Keys to Ultimate Performance

The weightroom offers some very fast solutions to athletes who need to put force into the ground for more time. An athlete whose nervous system isn’t wired to put force in the ground for a long period of time won’t be able to jump (off two feet) as well and accelerate as easily as an athlete who has this capability. In this sense, things like squats and deadlifts give athletes a quick neural skill boost, but this fades once an athlete is “up to speed” in this category of extended force application ability.

One of the things that is important to the long term success of a strength program is that in the process of building an athlete’s explosive skill-set, it shouldn’t contribute negative patterns in the process. We already talked a bit about this in point #1 on the influence of many traditional barbell programs on the feet. This next point is incredibly important since I work with many aquatic athletes, and focusing on the feet in the ground based sense isn’t nearly as helpful versus an athlete who is walks on the land for their sport.

To improve your performance in the weightroom that transfers to the field, and stay more injury free in the process, the ability to breathe well is a highly important aspect to the equation. In any weightroom lift, checking for the following three things is an important aspect of the athletic assessment:

- Does the athlete breathe through their chest or belly while lifting?

- What is the tension in their neck like while lifting?

- What is the tension in their jaw and face like?

I have some athletes who are literally fighting themselves the entire training session through chest breathing and neck tension. They have learned to move in a manner where they are will-powering themselves through the workout. Unfortunately, jaw and neck driven movement is associated with forebrain activity, which doesn’t transfer well to the world of fluid sport.

To really ramp up the effectiveness of the weightroom, I recommend teaching the “belly breath-glute squeeze” pair, where athletes learn to tense their glutes while breathing through their belly simultaneously. This sequence can and should be integrated into the daily workout, particularly those movements where the athlete is heavily loaded.

A quick sample can be used in the performance of the hang clean. At the top of the lift, where the athlete is standing upright, they will put some tension in their glutes, and release their belly into a few deep breaths. After this, perform the hang clean. By doing lifts in this manner, proper breathing, and a focus on the muscles at the center of movement are put at a premium.

Athletes should also be highly conscious of how much tension is running through various muscle groups in their body during particular lifts, namely the jaw, neck, shoulders and arms. Athletes with patterns of implosion overly tense these groups, while athletes who can explode from the center initiate movement from the glutes and psoas, while keeping the extremities relatively relaxed.

About the author:

Joel Smith is an assistant strength and conditioning coach at the University of California, Berkeley where he works with aquatic sports and tennis. Previously Joel was an NCAA track coach of 6 years while also working in strength and conditioning. He is the founder of Just Fly Sports, an informational site for speed and power based athletic development. Joel is the author of “Vertical Foundations” and “Vertical Ignition”, two books on the biomechanical and training aspects of vertical jump performance. In his spare time, he stays true to his track and field roots working with Diablo Valley Track Club, and doing private coaching throughout the San Francisco Bay Area.

Joel Smith is an assistant strength and conditioning coach at the University of California, Berkeley where he works with aquatic sports and tennis. Previously Joel was an NCAA track coach of 6 years while also working in strength and conditioning. He is the founder of Just Fly Sports, an informational site for speed and power based athletic development. Joel is the author of “Vertical Foundations” and “Vertical Ignition”, two books on the biomechanical and training aspects of vertical jump performance. In his spare time, he stays true to his track and field roots working with Diablo Valley Track Club, and doing private coaching throughout the San Francisco Bay Area.

0 Comments for “5 Ways to Get More Dynamic Transfer From the Weightroom to the Field”