Dealing with Muscular Imbalances around the

Lumbo-Pelvic-Hip-Joint

By: Dan Taylor

Introduction

The intention of this article is to offer a practical approach to those in the Strength and Conditioning field for dealing with muscular imbalances around the Lumbo-Pelvic-Hip joint. My experience is directly with NCAA Division I athletes, however I believe this approach can have positive affects at all levels and for all ages.

I think it is fair to say that this type of muscular imbalance affects just about every student athlete I deal with, however the scope of this article centers on Lacrosse players. For those unfamiliar with this sport it has many lower body requirements similar to soccer and utilizes upper body movements and energy systems much like Ice Hockey. Ultimately however it is a field sport that requires explosive hip extension just like any other.

Lower Crossed Syndrome

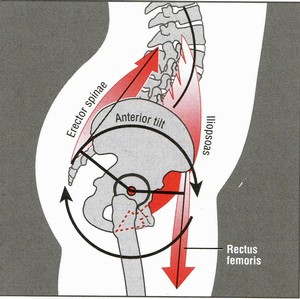

Muscular imbalances contribute to habitual overuse in isolated joints and faulty movement patterns, creating repetitive micro trauma, dysfunction and chronic injury. For the purpose of this article we are going to focus solely on the Lumbo-pelvic-hip postural distortion displayed through an anterior pelvic tilt (Fig.1). This type of imbalance is generally characterized in the U.S. by the term Lower Crossed Syndrome (LCS). Before breaking down the requirements of Lacrosse athletes it would be important to define what LCS is thereby allowing us to understand the ramifications of athlete’s who displays its characteristics. LCS is based on Dr. Vladimer Janda’s work in researching and understanding the pattern of muscular compensation and postural imbalances in the body. This type of LCS is defined as being performed by a force couple relationship between the hip flexors and low-back extensor muscles (1). The primary muscles affected in the anterior pelvic tilt are shown in table 1 (2).

| SHORTENED MUSCLES | LENGTHENED MUSCLES |

| Iliopsoas | Gluteus Maximus |

| Rectus Femoris | Hamstrings |

| Tensor Fascia Latae | Gluteus Medius |

| Short Adductors | Transversus Abdominus |

| Erector Spinae | Mutifidus |

| Gastrocnemius | Internal Oblique |

| Soleus | Anterior and Posterior Tibialis |

Table 1

Anatomy of Anterior Pelvic Tilt

The Men’s Lacrosse team I deal with is comprised of forty five, 18-21 year olds. The National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) states that these young athletes’s are only allowed to participate in training (on the field or in the weight room) a set number of hours per week. This can range from 8-20 per week depending on the time of year with weight room hours comprising of thirty to forty five minutes two to three times per week. The rest of the hours in the week are made up of class, study and free time, much of which is spent sitting in a hip flexed position. I make this point to show the fact not only is the “typical athletic position” one involving slight hip flexion but the majority of these young men’s day is spent in exactly the same position. This obviously plays into the LCS and causes a vicious cycle of improper length tension relationships typically causing hamstring strains, anterior knee and lower back pain (3). Lacrosse players need to have full extensibility of the hip complex to allow for powerful acceleration up field as well as the ability for dynamic direction change. Poor neural drive to the glutes caused by over activity of the hip flexors leads toward a myriad of injuries for this type of athlete and prior to my application of the following program the team had dealt with an abundance of hamstring pulls.

Program Outline

I am a big believer that a multi joint, ground based approach to training is the best concept when working with all athletes. However if one of the joints is impaired though a situation such as LCS, specific single joint work must be done to allow the overall plan to work effectively. The program itself is simple in concept flowing through three phases all to be completed in the same workout.

Phase 1: Soft Tissue Work and Flexibility.

This phase is focused on the areas commonly tight so as to be time efficient. Prior to static stretching foam rollers are used to gently apply force to the adhesions in the muscle fibers. The pressure caused by the weight of the limb being affected pressing into the surface of the foam will stimulate the Golgi Tendon Organ. This in turn creates autogenic inhibition, decreasing muscle spindle excitation and releasing the hypertonicity of the underlying musculature (4). Each area is rolled up and down the length of the muscle twice at a slow, even pace. The second part of the flexibility section requires the use of static stretches. I choose to include this form of stretching even though research has shown ability for it to decrease power output as I believe that athletic performance will be duly affected by chronic tightness and tonicity of muscles making lowered power output a secondary issue in this case. Each muscle group is stretched twice for a minimum of twenty seconds and should only be held at the maximum pointof mild discomfort. If pain is displayed the stretch should be terminated and that information passed onto the Athletic Trainers. This phase in its entirety should not take more than ten minutes.

| FOAM ROLL (Up & Down Each Muscle x 2) | STATIC STRETCH (2 x 20 Sec. Each) |

| Calves | Hip Flexors |

| I.T. Band | Erector Spinae |

| Hip Rotators/Glutes | Piriformis |

| Adductors | Pecs |

| Latissimus Dorsi | |

| Calves |

Table 2

Phase 2: Core Circuit

At this point the program will have inhibited the overactive muscles leaving a need to activate muscles that have become dormant and lengthened. Again for time efficiency I include this in the core section which also serves as a dynamic warm up before the commencement of the strength training exercises.

EXERCISE | SETS | REPS | TEMPO | REST INTERVAL |

Plank (Variations) | 3 | 30 sec. Hold | / | 0 sec. |

Cook Hip Lift* | 3 | 12 ea. Leg | Slow | 0 sec. |

Prone YTA* | 3 | 12 | Slow | 20 sec. |

Table 3

*The “Cook Hip Lift” is a single leg bridging motion with the opposite leg pulled in toward the chest to reinforce lumbar stability

**Exercise performed face down on a bench or stability ball beginning with a shoulder scaption movement (Y) followed by adduction (T) ending in a cobra type motion (A) with the scapula fully retracted and depressed.

As previously stated this phase is to be performed as a circuit therefore the first set of the ‘Plank’ should be followed directly by the first set of the ‘Cook Hip Lift’ concluding with the YTA motion. During the twenty second break the athlete can re-stretch chronically tight areas before performing the second set of the circuit.

|  |

Cook Hip Lift (Beginning) | Cook Hip Lift (End) |

Prone YTA (press Play to view) | |

Phase 3: Strength Training

There will now be a good level activation in the formerly deactivated muscle groups particularly for the case of Lacrosse in the glute complex. The strength training section of this workout changes dramatically ‘in-season’ to ‘off-season’ like most sports, table 4 is an example of the early in season program we have utilized this year in a twice a week format.

EXERCISE | SETS | REPS | TEMPO | REST INTERVAL |

Hang Clean | 2 | 6 RM | Fast | 90 sec. |

Split Squat | 2 | 8 RM ea. Leg | Controlled | 45 sec. |

Alternating Arm Dumbbell Press | 2 | 8 RM ea. Arm | Controlled | 45 sec.. |

Chin-up | 2 | 8 RM | Controlled | 45 sec. |

Shoulder Press | 2 | 8 RM | Controlled | 45 sec. |

Dumbbell Romanian Dead lift | 2 | 8 RM | Controlled | 45 sec. |

Table 4

Conclusion

The basic strategy that lies behind these three phases of training is simply one of inhibition, activation and integration. The foam rolling and static stretching methods are utilized to inhibit the hyperactivity in certain muscles allowing Phase II’s core circuit to activate the areas weakened by the neural dominance of their opposing muscle groups. Finally and most importantly for athletics we must integrate everything back into movement to prepare these young men and women to perform at their best.

Upon taking over the Strength and Conditioning department a year ago there has been a remarkable change in the lowered circumstance of hamstring injury as well as increased in speed shown in various tests. As with anything, improvements can always be made to exercise selection and programming. Future ideas for this type of program would include the ability for a individual structural analysis, possibly different exercise selection depending on the efficacy of the movement and the ability to test improved power output though the use of force plates or something similar.

I feel strongly that the fight against muscular imbalances of any kind is one that can not be won completely as there are many extrinsic factors that are out of the Strength Coaches control. However, constant reinforcement of good mechanics and creating awareness for the student body will lead to great results and a strong adherence to the program itself.

Recommended Athletes' Acceleration Products

—————————————————————————–

References:

Neumann, Donald A. (2002). Kinesiology of the Musculoskeletal System. St. Louis, MI: Mosby Inc. p.411

Clark, M., et al. (2004). NASM Performance Enhancement Specialist. Calabassas, CA: NASM. p 120

Sahrmann, Shirley A. (2002). Diagnosis and Treatment of Movement Impairment Syndromes.

St. Louis, MI: Mosby Inc. p. 161

Clark, M., et al. (2004). NASM Certified Personal Trainer Handbook. Calabassas, CA: NASM. p 212

About the Author:

Dan Taylor

Head Strength and Conditioning Coach

Siena College

www.siena.edu

0 Comments for “Dealing with Muscular Imbalances around the Lumbo-Pelvic-Hip-Joint”