Optimizing Long Term Athletic Development:

A Guide for Physical Preparation Coaches

By: Joel Smith

For those of us whose job is physical preparation, particularly those of us working with youth populations, we are more than aware that early specialization of skill is a huge downfall of modern Western sport.

Researcher M.F. Nagorni of the former USSR performed a study which showed that early specialization certainly leads to sport improvements, but also causes peaking at ages 15 or 16, where performance stagnates thereafter.

What is likely of further interest is the idea that not only should athletes be wary of specializing in a given skill too early, but also that the way an athlete is prepared in general physical means such as strength training and plyometrics is also of high importance to reaching one’s optimal physical potential in later peak performing years.

Research conducted by Olympic coaching legend Anatoli Bondarchuk has shown that developmental hammer throwers who gear the strength component of their training towards heavy maximal strength work will shoot ahead of peers who train with more conservative strength loads, particularly in the first two years of training this way. After a couple of years, however, the maximal strength athletes start to hit a ceiling, and are surpassed by their conservative strength training counterparts.

As important as it is to get athletes prepared for the immediate here and now, it’s also crucial to set them up well to succeed down the line! With this in mind, there are three major ideas to look at when working with athletes in terms of their long term development:

- Avoiding early peaking through overly intensive training means

- Training strengths and weaknesses appropriately

- The importance of multi-layered development

Avoiding “Early Peaking” Through Over-Intensification

So back to the work of Bondarchuk, showing that track athletes who focused on maximal strength gains will thrive in the short term, but also create a technical ceiling for themselves.

The cause of this?

Movement patterns. When we do any exercise, particularly ones that are intense and require a re-wiring of our movement patterns and neural wiring to adapt to heavy loads placed on the spine, we start to mold ourselves into those adaptations. Heavy loads are also highly stimulating, especially for beginners, and inhibit the learning of fine technique in one’s actual sport.

“Are these the patterns we are trying to wire in young athletes in the developmental process?”

What types of adaptations happen through repeated heavy loading? Here are some ways that athletes adapt to a large amount of heavy strength loads over a prolonged period of time:

- Increased selective recruitment timing of hamstrings and lower back muscles over gluteal muscles

- Decreased ability to reach elite levels of RFD (Rate of Force Development) in the specific coordination of one’s sport

- Different patterns of “irradiation” during movement (irradiation is a Pavel Tsatsouline term for the positive effect of one tensed muscle on another for absolute force production) which is a huge positive for barbell movements, but negative for other movements that require greater fluidity in sport skill muscle trains

- Increased supination in gait and slower turnover to the big toe in pronation

- Lowered ability to optimally learn a skill in the short term, while the neural inhibition that happens as a result of heavy lifting is in effect (think of feeling slow and sluggish as a byproduct of this neural inhibition)

As Frans Bosch has mentioned, it is critical to mention the potential negative effects of any movement or exercise, in addition to the positive. I find it interesting to see various charts of which types of lifting and plyometrics might transfer to which aspects of sport speed, such as acceleration versus maximal velocity, but there is rarely a suggestion of potential negative effects!

When working with athletes of any level, it is important to have an idea of how much barbell strength is truly required for any given sport skill on its highest level.

To this end, it is important to, at the very least, question how much barbell strength we are trying to pile on developing athletes at any point in time. I’ve seen suggestions of 5-10% improvements in barbell strength gains each year as a general guideline for developing athletes, which makes good sense to me, particularly as athletes approach their optimal strength standard.

We can make a few conversation points based on this ideal. It can change the way we might look at how elite athletes have progressed over time, and what ages are best to introduce particular training means.

One sport that I love digging into is track and field jumps. Stefan Holm, who cleared a bar of 7’10.5” in high jump while standing 5’11” is one of the most prolific high jumpers of all time. He didn’t start lifting weights until age 19, and once he did, he became very strong in those movements appropriate to high jump. Looking at his track record, he wasn’t huge on the world scene at age 19, but he definitely was in his late 20’s, with an Olympic gold medal and European records to his name. By establishing optimal patterns first, and intensifying later, one’s career almost always finds benefit.

Holm went from a PR of 7’1” at age 19 to 7’7” four years later, and eventually up to 7’10.5” 9 years later! Clearly, Holm may have done better early on through lifting weights, but how would heavy resistance training have effected his technical ability to jump with the technique dictated by his sport?

I don’t write this piece to discourage barbell training, and definitely not the process of getting athletes strong, since improving organism strength, as well as appropriate coordination against resistance is a huge part of what we do as preparation coaches.

What I do suggest in this situation is being familiar with the minimal dose required to make a positive change in the barbell realm. If you can get an athlete fairly strong using a single set system, such as the 1×20 system (Based on one set of 14-20 reps, or 2 sets of 8 at a “slow cooked” progression), why would you hit a developing athlete with more intensive multi-set barbell work that can be better utilized later on?

My friend Jeff Moyer who runs one of the best scholastic training programs around will utilize single set barbell training with beginning athletes (in conjunction with speed, plyometrics, vision and sensory work), and still see huge gains in their speed and explosiveness. It isn’t until they have run their course on single set work that he’ll start to incorporate more progressive multi-set methods such as Triphasic Training or Velocity Based Training.

Jeff’s checklist when going through progressing youth athletes in this regard is as follows:

1) Are they over volumized? Are we doing too much?

2) Are they recovering from training/practice?

3) Are there outside stressors? (school, parents, friends)

4) Do we need to rotate movements?

5) Do we need to rotate methods?

Finally, even in the sport of Olympic weightlifting, intensity restrictions are key in developmental systems. For example, according to Zygmunt Smalcerz, the Polish youth program for Olympic weightlifting has lifters under the age of 14 competing in “events” where they will snatch 50% of bodyweight and clean and jerk 75% in a technical competition that is scored like gymnastics. This ideal puts technique on the forefront before excessive intensification alters technical that is hard to fix later. It also makes for a different emphasis of competition.

Training Strength and Weaknesses Appropriately

Every athlete has strengths and weaknesses. Athletes move in sport in accordance with their strengths, and as they move through their career this “groove” of strengths gets deeper and deeper. For a very simple example, think of a big “weakness” area is when an athlete is posterior (good deadlift, high knee drive in sprinting) or anterior chain dominant (good squat and less knee drive in sprinting),that one chain is “weak”, while the other is strong.

The issue with strengths and weaknesses then becomes: 1. Coaches trying to give cues and instructions that take athletes out of their strengths and 2. Training that doesn’t reflect building an athlete in context of the balance that comes from addressing weaknesses (and liabilities), yet knowing when the time comes to focus heavily on one’s existing (and innate) strengths.

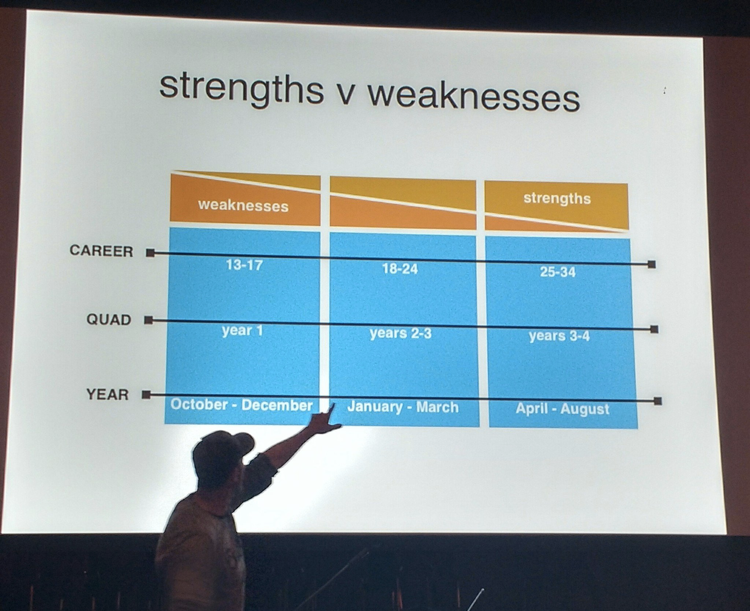

In listening to Stuart McMillan speak at the “Track Football Consortium 4”, he mentioned a great concept on long term development in context of strengths and weaknesses.

“Stuart McMillan speaking on topics of strength and long term development at the Track Football Consortium 4”

In the presentation, Stuart mentioned the difference between training athletes for short-term results, and long-term results, and the fact that they are different methods. He also talked about what it looks like to actually train an athlete with the long view in mind. This long view is represented by the above picture, of proportionally focusing more on weaknesses early in one’s development, and strengths later on. Even in advanced stages of training, athletes can still benefit by touching on weaknesses early in the season, also as shown above.

Examples of weaknesses that can be addressed in key points in training, in my own experience, are things like the following:

- Anterior or posterior chain dominance

- Bilateral or unilateral movement ability

- Lagging muscles in the key sling systems of movement (e.g. deep superficial, posterior sling system, and particularly the lateral chain)

- Foot and ankle strength and stiffness

Multi-Layered Development and High-Performance Alternatives

So what are the best ways to proceed in terms of planting the seeds of long term development with athletes of various ages? The biggest thing a great many athletes need is not more specific work, but rather, more general. Many athletes are far too specialized, and lack the athletic roots that will not only keep them healthier and prevent burnout, but also they lack the movement literacy that will allow them their highest potential in their given sport.

According to physical preparation legend James Smith link http://www.jtsstrength.com/articles/2011/09/14/super-child-part-i-early-childhood/, the fundamental aspects of athleticism are:

- Mobility

- Balance

- Coordination

- Kinesthetic sense

- Rhythm

- Relaxation

- Timing

Although we have a fascination with things that are relatively easy to improve in youth populations (weight on the barbell), there are other factors form a pure movement perspective that are incredibly important to the movement ability of an athlete, and therefore their long term success, as well as things that differentiate athletes on the highest level (maximal strength doesn’t differentiate non-strength sport results on the highest level).

James Smith has gone on to say that the three best formal sports in preparation of any athlete down the road are track and field, gymnastics and swimming, in addition to informal childhood ballgames.

Track helps athletes to learn the skills of acceleration, maximal speed, jumping and sequential application of force (throwing). On top of this, it is no surprise that the majority of successful football teams in the nation, such as Alabama and Ohio State have a huge contingent of very successful high school track athletes on their rosters. Speed is far more important than the 1000lb club when it comes to an athletes collegiate, and pro potential.

Every year I am part of a seminar in Chicago Illinios that is largely founded on the ability of track and football to enhance each other, and argues against specializing in one or the other for the entire year!

Gymnastics is a great sport in very early development, as it assists with ground based body and trunk control. More and more coaches are utilizing basic gymnastics drills in developmental phases to help assist with this very common weakness of body control and relative strength in early season training. The easiest way to incorporate it is during a warmup.

Jay DeMayo of the University of Richmond has a great system of using gymnastic work along with loaded carries as part of his warmup sequences, therefore killing two birds with one stone, as loaded carries is also an important movement and aspect of core control.

The video below highlights some examples of this type of training, and clearly the majority of it is out of the league of many athletes, however, I find great use of many of the floor and bar based exercises, such as AG walks, body levers, hanging leg lifts and front lever pull variations, particularly with my swim athletes.

In watching video of the long term development of Japanese swimmers who, pound for pound, are some of the best in the world, the youth incorporate mat based gymnastic work into their routines for added body control.

Along the lines of swimming this third early sport to participate in may not be quite as obvious to long term development, but swimming maximizes an athletes ability to produce force through the trunk and spine with no solid external stimuli (how well can an athlete manage internal forces and coordination within the body itself). It also requires large ranges of motion in the upper body. Swimming also can happen before an athlete can even walk, and is the groundwork for many of the athletic qualities James has mentioned.

Clearly, physical preparation coaches in youth settings don’t have a pool sitting around at many of their facilities, but there are some good take home ideals that we can derive from all this. Ultimately, we need to spend more time teaching athletes how to move properly, operate contralaterally and perform the basic human movements well, such as crawling, carrying, crouching, hinging, jumping, sprinting. We can teach core control through gymnastics elements such as basic tumbling, handstands and bar work. Teaching children how to properly sprint may be one of the biggest impactors of their movement ability down the line.

Even within the scope of the weightroom, rhythm, relaxation and timing can all be trained under the barbell. Isometric work is some of the best way to teach kids positioning and posture under load, and once this is established, athletes can perform basic tensioning and release movements with light to moderate weights early in the developmental process.

Finally, too many athletes compete too much too early, and don’t take the proper time to lay down a solid general ground work of things. According to Mark McLaughlin of PTC and Omegawave North America,

“You can not have a yearly schedule of physical development which is 70-100% competition and the balance physical preparation. The general physical development then is sacrificed for short term gains (wins/losses) at a time when it really does not matter.”

The competition and training schedule must be kept in check, and this is something that clearly goes beyond the work that physical preparation coaches are doing, and is in the hands of educating sports parents and coaches alike. Young athletes need to balance the amount of competitions they are in, and make sure there is time for both development of all-around skills, as well as fun and games.

Ultimately, one’s success is built on the basework they have laid down, and as coaches, the more we are aware of what makes one successful, the better we can help them prepare.

About the Author:

Joel Smith is an assistant strength and conditioning coach at the University of California, Berkeley where he works with aquatic sports and tennis. Previously Joel was an NCAA track coach of 6 years while also working in strength and conditioning. He is the founder of Just Fly Sports, an informational site for speed and power based athletic development. Joel is the author of “Vertical Foundations” and “Vertical Ignition”, two books on the biomechanical and training aspects of vertical jump performance. In his spare time, he stays true to his track and field roots working with Diablo Valley Track Club, and doing private coaching throughout the San Francisco Bay Area.

Joel Smith is an assistant strength and conditioning coach at the University of California, Berkeley where he works with aquatic sports and tennis. Previously Joel was an NCAA track coach of 6 years while also working in strength and conditioning. He is the founder of Just Fly Sports, an informational site for speed and power based athletic development. Joel is the author of “Vertical Foundations” and “Vertical Ignition”, two books on the biomechanical and training aspects of vertical jump performance. In his spare time, he stays true to his track and field roots working with Diablo Valley Track Club, and doing private coaching throughout the San Francisco Bay Area.

0 Comments for “Optimizing Long Term Athletic Development”