Balance Training Revisited

By: Phil Loomis

When you hear balance training it likely conjures up images of athletes standing on one leg and on some type of unstable surface i.e., wobble board, Bosu, soft foam pad…

We know balance is important in sport but what are we really talking about when we reference this quality?

Rogers et al., 2013 stated that there are a variety of ways to evaluate balance and fall-risk, and each older adult should be regularly screened in order to evaluate any changes in the ability to maintain postural stability.

In terms of “balance” training what we are really looking to improve with athletes is their ability to maintain and regain postural stability.

According to Huang et al., 2013 postural stability can be defined as the ability of an individual to maintain their center of gravity within the base of support. It involves feedback from the sensorial systems which determine continual neuromuscular changes.

For the remainder of this article, I ask that whenever the word “balance” is used view it through this “postural stability’ lens.

Here are a few things to consider from published research with respect to “balance” and sport performance:

Malliou et al., 2010 showed that a tennis training session did not affect significantly the tennis players’ balance ability/performance. That said, the authors of this study pointed out their subjects were elite tennis players free of injuries in the lower limbs for the past 3 years.

Gioftsidou et al., 2006 also found in contrast to the notion of a link between fatigue induced by a soccer training session or game and injury caused by impaired balance. Their subjects were healthy soccer players.

Hahn et al., 2007 showed that one-leg standing balance in basketball players was positively correlated with the years of participation in basketball, and suggested that practice may induce significant adaptive effects on standing balance.

Johnston et al., 1998 concluded that fatigued individuals are at increased risk of injury because of loss of balance. Avoidance of fatigue and preconditioning may prevent injury. The subjects in this research were healthy subjects (not active athletes) between the ages of 20 to 39.

Notarnicola et al., 2016 selected young male basketball players, who were currently participating in basketball at least 1 year before the study, no lower extremity musculoskeletal injuries, no history of head injury or of pre-existing visual, vestibular, or balance disorders. They concluded that stability improved after 12 weeks of training, even for those conditions for which no specific training was done to improve.

The Gioftsidou study above with soccer players also demonstrated increased balance ability in their two intervention groups (groups that participated in a balance training program).

A key component of balance is proprioception, i.e. joint positional sense. Relph et al., 2016 concluded that elite athletes who have had an ACL injury, reconstruction, rehabilitation and returned to international play demonstrate lower Joint Positional Sense ability compared to control groups. It is unclear if this deficiency affects long-term performance or secondary injury and reinjury problems.

Garrison et al., 2013 concluded that participants with a UCL (medial elbow ligament) tear demonstrated decreased performance for their stance and lead lower extremities during the Y Balance Test. The subjects in this study were experienced high school and collegiate baseball players. 30 athletes with a UCL tear were compared with 30 control athletes (no UCL tear).

Guskiewicz et al., 2001 concluded that athletes with cerebral concussion demonstrated acute balance deficits, which are likely the result of not using information from the vestibular and visual systems effectively.

To wrap up all of this research in a practical bow…

Injuries change everything!

Injuries have negative effects on joint position sense or proprioception and this “internal” sense is a key component of balance.

It is also important to consider the concept of regional interdependence . A seemingly unrelated elbow injury negatively affected the balance of both lower extremities in competitive baseball players.

Pre and post “balance” screening procedures can be very important in terms of return to play protocols. Especially with respect to athletes that have sustained concussions.

Train to play or play to train?

It appears that athletes with a steep to moderate training history, and currently active/training, and that are healthy (no injuries) have very good “balance” and they maintain it even under conditions that may cause fatigue.

Further it appears that “just” playing a sport competitively may foster significant improvements in “balance”, even without any specific interventions.

On that note I love this comment by Tony Moreno professor of Kinesiology at Eastern Michigan University and Long-Term Athletic Development expert:

You can’t compare the “balance” of a world class surfer riding a 20 ft. wave to the “balance” LeBron James needs on a fall-away jumper with 2 seconds left. They are different motor control problems.

Balance requirements, then, are task specific!

While both the Notarnicola and Gioftsidou groups demonstrated improved stability in their subjects that participated in balance training interventions, there is no way to claim it actually transferred to on-court/field performance (the researchers did not make any such claims)…

That is not to say that a general or non-specific “balance” training program is ineffective…

But is this “functional” training or just a bunch of stuff that looks cool and allows you to improve your ability to balance on a wobble board?

Righting or fighting?

In sport when an athlete is knocked off balance they reflexively seek to regain equilibrium by repositioning their feet/center of mass to establish a steady base of support. This repositioning is essential because it allows for an effective response to the action/reaction that caused them to lose balance initially. This state of imbalance may have been caused by: physical contact from an opponent, like a linebacker hitting a running back as he explodes through a hole, a shortstop lunging toward his right to backhand a ground ball, or a tennis player that has slid across the court to hit a wide backhand stroke. In each instance the athlete will temporarily find themselves in a state of imbalance but all will react by repositioning their body in order to “get back in the play.”

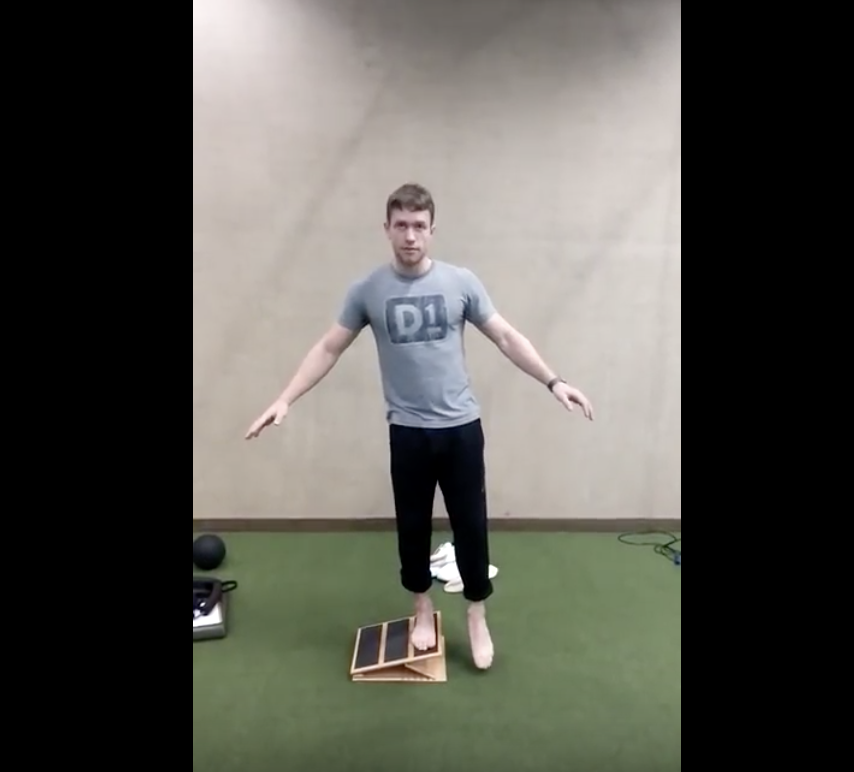

Here is an example of a common “balance” training exercise that you may see:

In the above video the athlete is “fighting” to hold his balance. If an athlete attempted to regain his/her balance like this in a competitive setting it’s safe to assume the results would not be in their favor.

Next is an example with a different objective: right don’t fight!

This is what we want to encourage from our athletes… Get right fast… so you can make a play!

I’m not saying there’s anything wrong per se about training on unstable surfaces but when you have limited time to work with athletes it may not be the best use of your time.

Consider this comment from Sue Falsone:

When athletes are coming back from an injury, balance and proprioception are often the biggest challenges. They also struggle with maintaining equilibrium. To restore this in the past we mistakenly had them spend a lot of time on balls and balance boards – tippy surfaces we thought would help restore reactive balance. *

It would take me an hour to list all of Sue Falsone’s credentials but she is an authority in terms of working with athletic populations.

Think about what happens while standing on an unstable surface… When an athlete begins to lose control in many instances the surface adapts to them. In some ways it almost seems easier to maintain your balance on an unstable surface. As you can see in the videos below while these exercises may seem challenging he can likely do these “all day” …

Alternatively, if an athlete’s foot is interacting with a surface that does not move i.e., a stable surface and they begin to lose control, their body must adapt to the surface to maintain their balance.

There are a few other things well worth considering with respect to balance training:

Unstable versus uneven surfaces

Imagine an infielder in baseball who has to retreat on a fly ball into the outfield. He starts on the infield dirt and as he runs back he may step on the lip of grass where the outfield begins. If it’s a grass outfield the field may have random bumps/divots and the surface may be slightly sloped. The infielder has to track the ball all while managing the subtle (and if the turf is in poor condition, no so subtle) changes in the terrain. The ground is not unstable but it is uneven.

In field sports that play on grass surfaces this is a common sensorimotor demand (the ever-changing terrain) on the nervous system. In training it makes a lot of sense to simulate surfaces that athletes will encounter on the field. Aside from water sports and a few winter sports the surface is rarely stable.

The best solution here is to train balance on a grass field. Another option that I personally love is the use of slant boards. These are stable surfaces that are uneven and provide you with the option of changing the angle of the slope. If you are familiar with the “anti” concept in core training (anti-flexion, extension, rotation) slant boards can be utilized to train anti-eversion/inversion of the ankle. I find this particularly useful in baseball and tennis populations due to the demands placed on the foot/ankle complex. Think about the scenario above: the infielder encountering a variety of changes in the surface that he can’t anticipate but must be prepared for; random and varying degrees of ankle eversion and inversion.

Again, from Sue Falsone:

Having an athlete train on unstable surfaces is not wrong; it is just one element in a list of proprioceptive variables that we can manipulate.

Uneven surfaces are just as stimulating as unstable surfaces. *

The vestibular system

Along with vision (sight) and proprioception (touch) the vestibular system is a key component of sensory input. Optimal sensory input allows for optimal motor output… Sensory information about motion, equilibrium, and spatial orientation is provided by the vestibular organs, which include the canals in the inner ear. These canals detect gravity, linear movement and rotational movement.

As coaches we can stimulate and challenge the vestibular system by asking our athletes to change head positions. Athletes can perform single leg activities or other movement patterns while turning their head up and down, left and right, up and right, down and left, etc. You can also have the athlete keep their head still but have them move their eyes up, down, right, left, up to the right, down to the left, etc.

Movement options with head movements to challenge vestibular system and postural stability

Changing head positions is extremely relevant to simulating on field/court demands. Think about a center fielder who has to retreat on a deep fly ball that is going over his head. He retreats to sprint across a grass outfield that has a subtle but ever-changing terrain, while sprinting backwards his head is turned in the opposite direction as he tracks the ball off the bat. While sprinting back he can “sense” the outfield wall getting closer as he steps from the grass onto the dirt warning track… Just before he contacts the wall he snaps his head around to watch the ball into his outstretched glove as his feet leave the ground and then… BANG! He hits the wall, temporarily closes his eyes, and lands back on the dirt warning track slightly staggered by the blow. He must quickly gather himself in order to throw the ball back to the infield to hit a cut-off man yelling “3,3”.

The above scenario is the ultimate sensorimotor experience and a highly relevant and “functional” challenge to an athlete’s “balance.”

Rolling patterns and even flowing Yoga (or mobility circuits) particularly in the transitions between poses are also very effective methods to stimulate and challenge the vestibular system specifically and more generally the entire sensorimotor system.

In summary, there is much more to balance training than challenging an athlete’s single leg proficiency on unstable surfaces. There are plenty of options available to you. Make sure you’re applying those that are most relevant to the populations that you coach.

A few parting thoughts…

In my experience, most commercial slant boards are too steep, even on the lowest setting. You’ll want to find boards that allow you to subtly adjust the slope. I’ve had mine quite a long time and they were made by a local carpenter to my exact specifications.

You’ll also want to perform these drills barefoot…

No shoes or socks! The sole of the shoe will “stick” to the surface and your foot will slide inside the shoe. You must “feel” the surface to get the most benefit. Ideally, I slide these slant board movements in early during the warm-up and often lead with them as I find they do a great job of “tuning” the nervous system. Which leads to my parting thought…

Step one in any sensorimotor enhancement program starts from the ground up! The function and health of the feet are a critical piece. But that’s a story for another day. Stay tuned…

Reference:

*“Chapter 7 Somatosensory Control.” Bridging the Gap from Rehab to Performance, by Sue Falsone and Mark Verstegen, On Target Publications, 2018, pp. 127–128.

About the Author

About the Author

Coach Phil Loomis is a fitness professional and nutrition coach at Life Time Athletic in Bloomfield, MI as well as a strength and conditioning coach for the Michigan Red Sox in Birmingham, MI. He was also the head coach and CEO of Forever Fit in Troy, MI. He is currently certified as a Strength and Conditioning Specialist, Youth Athletic Development Specialist, Speed and Agility Specialist, Corrective Exercise Specialist, and a Precision Nutrition Certified Coach among others.

Coach Loomis played Division 1 college baseball and it was then that he developed the appreciation for the impact that off-field performance training and nutrition can have for developing athletes. His passion for youth and sports performance lead him to start Forever Fit. His training experience has lead him to develop a deep appreciation for corrective exercise and long-term athletic development strategies. He specializes in functional anatomy and bio-mechanics as they relate to program design and corrective exercise; youth athletic development; and rotational/overhead athlete performance enhancement.

Recommended Athletes Acceleration Products

| |

| Complete Sports Training |

0 Comments for “Balance Training Revisited”