Speed Training Methods for Hockey

Kevin Neeld, MS, CSCS, USAW, LMT, PRT

Head Performance Coach, Boston Bruins

Speed is arguably the most critical physical capacity in ice hockey. In other words, no single physical attribute will dictate a player’s success at a given level more than speed. As a result, training PROPERLY for speed is an absolutely essential part of a player’s development.

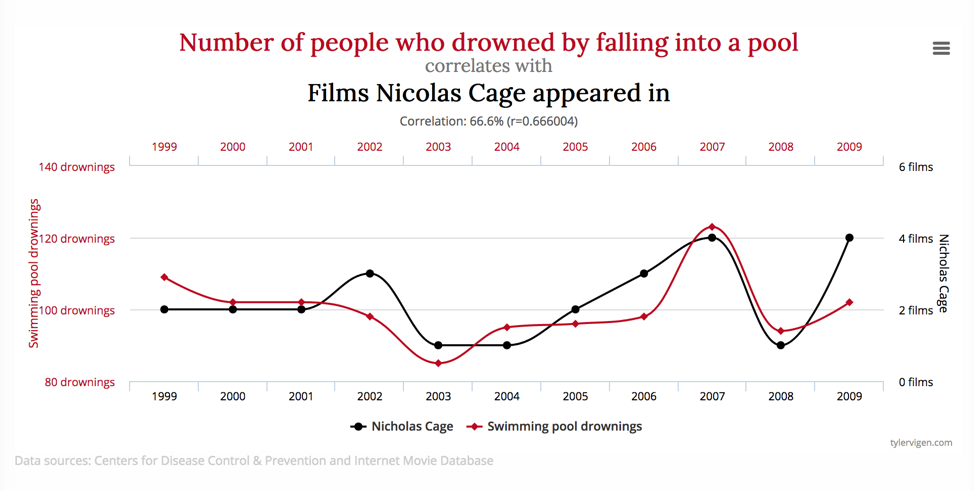

In an attempt to understand what factors may predict faster skaters, several studies have looked at the relationship between off-ice sprinting speeds and on-ice skating speed and found that there’s a moderate correlation. In other words, faster runners are generally faster skaters, but there is a lot of gray area. One of the very first things students learn in any introductory statistics or research methods course is that “correlation does not imply causation.” Simply, just because two things are related does not mean that one directly explains the other. For example, consider the below “Spurious Correlation” example from TylerVigen.com:

Interestingly, this correlation is actually higher than most reports of the relationship between off- and on-ice sprinting speed. And while it’s possible that people are so offended by Nicolas Cage’s acting that they’d prefer sleeping underwater, it’s more likely that these two factors have absolutely nothing to do with each other except that they had a peak during the same year, and a regression back toward more standard values the next.

Sprinting On vs. Off the Ice

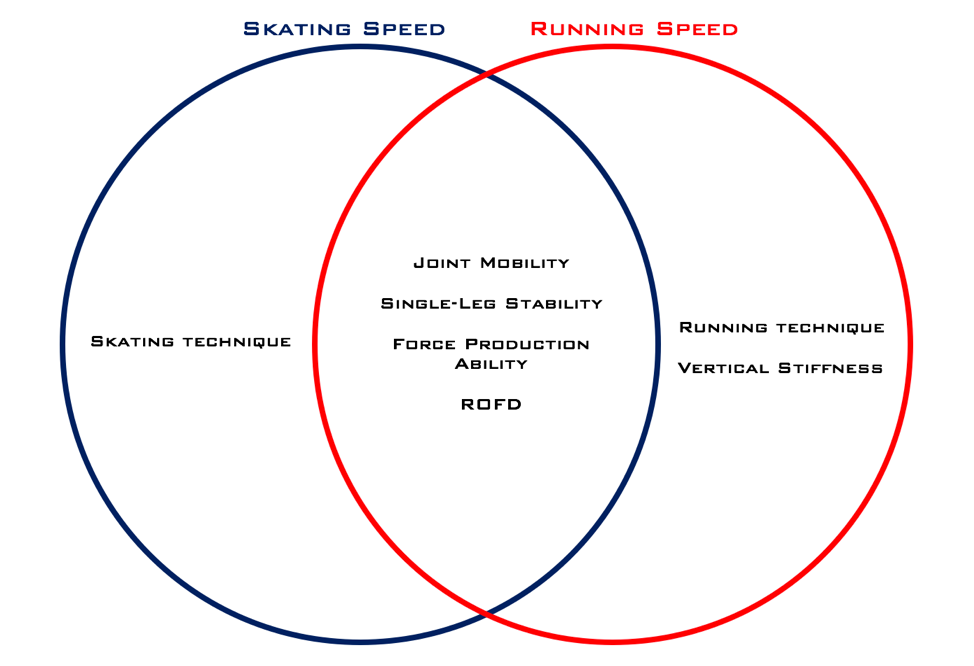

In recognizing all of this, it’s important to look at what common factors may lead to speed both off- and on-the ice, and which may be more specific to one over the other. To be overly simplistic, the fundamental physical capacities of joint mobility, single-leg stability, force production ability, and rate of force development (ROFD) are likely to positively contribute to speed on and off the ice. Technical elements are more specific to each individual domain.

This may seem like common sense, but it has some important practical considerations. Namely, spending significant amounts of time improving running technique may lead to improvements in off-ice sprinting times, but it likely will not lead to any notable transfer to the ice. Hockey players should work to become competent, but not perfect sprinters, and allocate any additional time for technique work to maximize their efficiency on the ice.

Speed Training For Hockey: Get a copy of your book here.

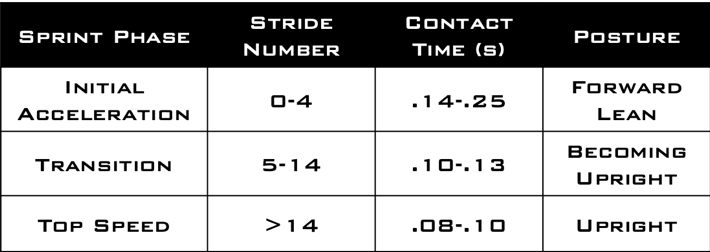

Another important consideration is how the running stride changes as players accelerate toward and reach top speed. A study examining the movement characteristics of sprinters found that as early as the 5th stride, their posture was becoming more upright, and the ground contact time was approaching 10ms. They also noted that stride rate increased up to the 4th stride and then remained constant at ~4.87 strides per second thereafter.

Nagahara, et al., 2014

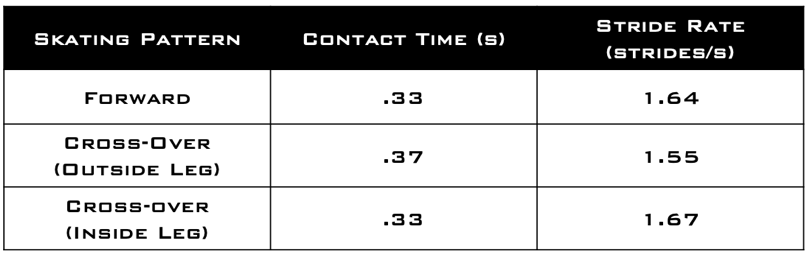

In contrast, both forward and crossover skating patterns require a significant forward lean, have longer “ice contact times” and a slower stride rate. Skating also involves more of a “pushing” stride pattern. It doesn’t have the same vertical force absorption component characteristic of top speed running.

Robert-Lachaine, et al., 2012

Off-Ice vs. On-Ice Sprinting Summary

There are a few important takeaways here. Compared to sprinting, skating involves:

- More lateral and rotational movement through the hips

- A consistent forward lean

- Longer ground contact times and slower foot turnover

- More of a “concentric” pushing emphasis, than a vertical stiffness/stretch reflex emphasis

For a comprehensive program designed to get your hockey athletes faster,

check out this book: Speed Training for Hockey.

Training Implications

Having a clearer understanding of the unique characteristics of skating can directly inform exercise selection. Below are a few basic examples of small adjustments to commonly programmed exercises/strategies to improve the transfer to on-ice speed :

Sprinting

The majority of sprint work should be performed between 10-20 yards. Accelerations within this distance emphasize the posture, longer contact time, and more piston-like pushing patterns that more directly translate to skating.

Starting sprints from front-facing and lateral half-kneeling positions will further exaggerate these characteristics. Starting from back facing, side standing open up, or side standing cross-under positions can be used to further emphasize some of the lateral and rotational pushes more characteristic of both linear and cross-over skating.

Cross-Under Start, emphasizing a “push under” with the front leg, similar to the push in crossover patterns on the ice.

Jumping

Hockey players will benefit more from jumping exercises initiated from deeper hip and knee flexion angles (i.e. from angles resembling the skating stance), and longer ground contact times.

There are several strategies to achieve this. First, exercises intended to minimize ground contact time and/or knee and hip flexion (e.g. pogo hops, drop jumps, etc.) should be used sparingly.

Several traditional jumps, such as box jumps, vertical jumps, and lateral and diagonal bounds, can be started from the down position to further emphasize the concentric “pushing” portion of the movement.

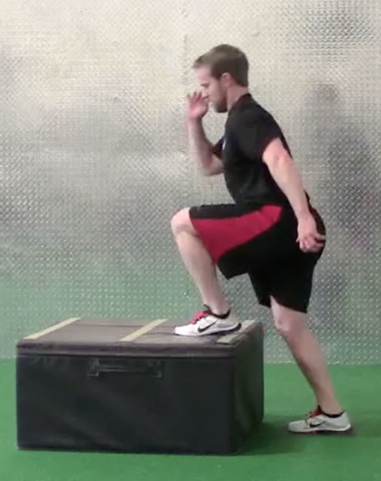

One of the biggest changes I’ve made to my programs over the last 5 years is including more step-up variations. Step-Up Jumps meet the overwhelming majority of the criteria discussed so far (i.e. single-leg pattern initiated from a position of deep hip and knee flexion with a concentric pushing emphasis), and are fairly easy to teach. Box heights can be adjusted to account for strength differences and to ensure a clean movement pattern.

Set-Up for a Step-Up Jump. If the jump doesn’t look smooth (or fast), transition to a lower box with more of a forward learn over the front foot.

Sled Pushes/Drags

Sprinting against resistance can lead to several changes that more closely resemble skating characteristics. For example, one study noted that “sled towing” with 32% of body weight resulted in a stride frequency ~1.7/second and ground contact times ~.22-.25 (Lockie, Murphy, & Spinks, 2003). This was around a 20% increase in ground contact time compared to unloaded sprinting, leading the authors to state that, “…as resistance is increased, contact with the ground is lengthened considerably.” The longer ground contact time coincided with an increase in trunk lean, hip range of motion, and knee extension, and decreased flight time 40-50%.

Sled drags, loaded properly, force the player into an acceleration position similar to skating

Wrap Up

Many training programs pull speed training methods directly from track and field. These certainly have a place, but linear and crossover skating are unique movement patterns that have several important distinctions from running. A deeper understanding of these characteristics can help coaches make fairly subtle programming adjustments that will lead to a better transfer of off-ice speed training efforts to actual skating speed.

References

Lockie, R., Murphy, A., & Spinks, C. (2003). Effects of Resisted Sled Towing on Sprint Kinematics in Field Sport Athletes. Journal of Strength and Conditioning, 17(4), 760-767.

Nagahara, R., Matsubayashi, T., Matsuo, A., & Zushi, K. (2014). Kinematics of transition during human accelerated sprinting. Biology Open, 3, 689-699.

Robert-Lachaine, X., Turcotte, R., Dixon, P., & Pearsall, D. (2012). Impact of hockey skate design on ankle motion and force production. Sports Engineering, 15, 197- 206.

About the Author

Kevin Neeld is currently the head performance coach for the NHL Boston Bruins.

Kevin Neeld is currently the head performance coach for the NHL Boston Bruins.

He grew up in West Chester, PA and played hockey for the Wlimington Typhoon for several years before eventually transitioning to the Junior Flyers.

When he was 14, he was fortunate to be “given a chance” by a coach that was ahead of his time on the training and power skating side of things. Kevin completely overhauled his athleticism through a focused off-season of training. He knew then that he wanted to make a career out of helping other hockey players to do the same. He also spent that summer running power skating and skill development clinics. This not only helped his own skills, but also gave him an appreciation for how to break down skills to better teach them in group and individual settings.

Since that experience, Kevin’s been incredibly passionate about athletic development in general, but more specifically about on- and off-ice hockey development. He believes EVERY athlete can get better.

Kevin’s dedicated his career to helping aspiring athletes fulfill their potential.

Athletes Acceleration Recommended Product

For a step-by-step blueprint to developing game changing speed, quickness, and stamina, check out the book, Speed Training for Hockey, by Boston Bruins Head Performance Coach, Kevin Neeld.

0 Comments for “Speed Training Methods for Hockey”